Manetho’s SECOND DYNASTY of nine kings from Thinis presents even more intractable problems than its predecessor. Four of the Manethonian names are recognizable, despite grave distortion, in the Ramesside king-lists, though it needed a demonstration of great acumen to show how Manetho’s Tlas originated in a King Weneg known only from fragments of bowls stored in the underground galleries of the Step Pyramid. The king-list enumerate eleven kings in place of Manetho’s nine, but of these only four find confirmation in the monuments. The order of the first five kings is established with certainty, but the existing remains ignore Boethos and Kaiechos and offer us in their stead a Hotepsekhemui and a Nebre’. The former name is interesting, for it signifies ‘The Two Powers are pacified’ and we shall soon find evidence that expression implies recovery from a precedent condition of turmoil or anarchy; the reason for the transition from Dyn. I to Dyn. II can thus be divined. Though Boethos is unknown to the contemporary hieroglyphs, the form Bedjau in which the king-lists introduce it to us is found on an Old Kingdom writing-board in front of five well-known kings of Dyns. IV and V. With the third king of Keyn II we reach a sequence of three kings, namely Binothris, Tlas and Sethenes, where the monuments, the king-lists, and Manetho are in agreement, for Binothris is evidently the extended equivalent of the hieroglyphic name which to the eye appears to read Nutjeren, though scholars have argued in favor of the transcriptions Ninetjer or Neterimu. Concerning Tlas we have already spoken, and Sethenes is undoubtedly the Send to whom we shall return later; a most curious name since it means ‘the Afraid’. It may here, however, be added that Ninetjer presides over the fourth line of the Palermo Stone in such a way as to show that he reigned not much less that thirty years.

With one exception of Nebka, the remaining six names in the king-lists are a mystery, since not a trace of their bearers has been found elsewhere. Neferkare, Manetho’s Nephercheres, may indeed be fictitious, since the reference to the sun-god Re’ in its termination seems to point to later times, and there were in fact monarchs so called in Dyns. VI, VIII, and XXI. Nor need there be any perplexity about ‘Aha which appears to be the correct reading in the Turin Canon, an isolated occurrence possibly the result of corruption of some kind. On the other hand Neferkaseker, Hudjefa, and Beby of the Ramesside tradition cannot be dismissed quite so easily, the more so since the Canon attributes to them reigns of substantial length. It can only be supposed that they were deemed by Manetho and his forerunners to be superior to those of certain Pharaohs of the south who completely ignored them. To those Pharaohs, four at most and possibly only two, we now turn. At Umm el-Ka’ab, Petrie excavated at opposite ends of the protodynastic cemetery a small tomb belonging to a King Peribsen and an exceptionally elongated one belonging to a King Khasekhemui. The first of the former monarch showed the extraordinary feature of being surmounted by the Seth-animal instead of the usual falcon of Horus, while the second of Kha’sekhemui exhibited the Seth-animal and the Horus-falcon face to face, each wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. Explanations which have already been given, as well as the analogy of Queen Neit Hetepu commented upon, leave no doubt as to the meaning of this procedure, and this is born out by the name Kha’sekhemui itself and by the addition Nebuihotpimef which follows as part of the name. In translation the entire combination runs ‘The Two Powers are arisen, the Two Lords are at peace in him’. In other words, King Kha’sekhemui now embodies in himself the two gods between whom hostility had arisen through Peribsen’s repudiation of his traditional ancestor in favor of that Deity’s arch-enemy. Clearly, great disturbances lie at the back of these revolutionary moves, but it is impossible to diagnose their nature. In the distant past, Horus had been particularly associated with the Delta, while the cult of Seth was localized near Nakada (Ombos) in Upper Egypt. Yet it seems impossible to interpret the facts as a struggle between Two Lands in which Peribsen had to content himself with being the ruler of Upper Egypt. Had their been such a contest between north and south, would not Peribsen have asserted his pretension to be the embodiment of Horus all the more vigorously? A further complication is that on certain sealings of Peribsen the Seth-like animal is given the name Ash, and this is known to have belonged to the Libyan counterpart of the Ombite. It was hinted that this cluster of kings might involve on two instead of four and we must now follow up on that possibility. In the tomb of Peribsen there were found jar-sealings of a Horus Sekhemyeb, and it was at first supposed that Sekhemyeb was the Horus-name of Peribsen himself, though such a supposition was contradiction by the presence of Seth on the serekh inmost of the sealings, as well as on the two fine granite stelae which had stood in front of the tomb-chamber. A subsequent dig, a little distance away, brought to light a king Sekhemyeb Perenma’e whom now was understood to be a predecessor of Peribsen.

With one exception of Nebka, the remaining six names in the king-lists are a mystery, since not a trace of their bearers has been found elsewhere. Neferkare, Manetho’s Nephercheres, may indeed be fictitious, since the reference to the sun-god Re’ in its termination seems to point to later times, and there were in fact monarchs so called in Dyns. VI, VIII, and XXI. Nor need there be any perplexity about ‘Aha which appears to be the correct reading in the Turin Canon, an isolated occurrence possibly the result of corruption of some kind. On the other hand Neferkaseker, Hudjefa, and Beby of the Ramesside tradition cannot be dismissed quite so easily, the more so since the Canon attributes to them reigns of substantial length. It can only be supposed that they were deemed by Manetho and his forerunners to be superior to those of certain Pharaohs of the south who completely ignored them. To those Pharaohs, four at most and possibly only two, we now turn. At Umm el-Ka’ab, Petrie excavated at opposite ends of the protodynastic cemetery a small tomb belonging to a King Peribsen and an exceptionally elongated one belonging to a King Khasekhemui. The first of the former monarch showed the extraordinary feature of being surmounted by the Seth-animal instead of the usual falcon of Horus, while the second of Kha’sekhemui exhibited the Seth-animal and the Horus-falcon face to face, each wearing the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt. Explanations which have already been given, as well as the analogy of Queen Neit Hetepu commented upon, leave no doubt as to the meaning of this procedure, and this is born out by the name Kha’sekhemui itself and by the addition Nebuihotpimef which follows as part of the name. In translation the entire combination runs ‘The Two Powers are arisen, the Two Lords are at peace in him’. In other words, King Kha’sekhemui now embodies in himself the two gods between whom hostility had arisen through Peribsen’s repudiation of his traditional ancestor in favor of that Deity’s arch-enemy. Clearly, great disturbances lie at the back of these revolutionary moves, but it is impossible to diagnose their nature. In the distant past, Horus had been particularly associated with the Delta, while the cult of Seth was localized near Nakada (Ombos) in Upper Egypt. Yet it seems impossible to interpret the facts as a struggle between Two Lands in which Peribsen had to content himself with being the ruler of Upper Egypt. Had their been such a contest between north and south, would not Peribsen have asserted his pretension to be the embodiment of Horus all the more vigorously? A further complication is that on certain sealings of Peribsen the Seth-like animal is given the name Ash, and this is known to have belonged to the Libyan counterpart of the Ombite. It was hinted that this cluster of kings might involve on two instead of four and we must now follow up on that possibility. In the tomb of Peribsen there were found jar-sealings of a Horus Sekhemyeb, and it was at first supposed that Sekhemyeb was the Horus-name of Peribsen himself, though such a supposition was contradiction by the presence of Seth on the serekh inmost of the sealings, as well as on the two fine granite stelae which had stood in front of the tomb-chamber. A subsequent dig, a little distance away, brought to light a king Sekhemyeb Perenma’e whom now was understood to be a predecessor of Peribsen.

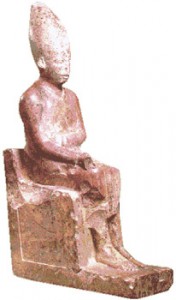

Later the full name was found on fragments from the Step Pyramid. There is much likelihood in Grdseloff’s guess that Sekhemyeb Perema’e was merely the name of Peribsen before he abandoned his allegiance to Horus in order to become the fervent worshipper of Seth. More difficult is the question of the Horus Kha’sekhem whose monuments are confined to Hieraconpolis. They consist of a broken stela, two great stone bowls, and two seated statues of limestone and slate respectively. The slate statue is the more complete, but half the face is broken away, whence the features are better seen on that of limestone now in Oxford. The pose, the style, and the workmanship are such as would have been impossible at the beginning of Dyn. II and go far towards corroborating the position of this king towards its conclusion. The stela reveals who these enemies were. Attached to the same bolsterlike oval as is seen on the palette of Na’rmer, it clearly indicates Libyan foes. The design scratched on the bowls shows the vulture-goddess Nekhbe of El-Kab presenting to Kha’sekhem the symbol for the unification of the Two Lands, while her hinder claw rests on a circular cartouche enclosing the signs for Besh. This Besh is more likely to be Kha’sekhem’s personal name than the name of a conquered country or chieftain. The right side of the design is occupied by the hieroglyph for ‘year’ accompanied by the words ‘of fighting and smiting the northerners’. On all these objects the white crown of Upper Egypt is worn. What was the relation of Kha’sekhem of Hieraconpolis to Peribsen on the one hand to Kha’sekhemui on the other? The hypothesis at present is that Kha’sekhem was the immediate successor of Peribsen, whose name does not occur at Hieraconpolis, and that he won back the Delta and was followed by Kha’sekhemui. But would this later king, if preceded by a worshipper of Horus, have recalled in his name the former dissension between Horus and Seth? The possibility that the Horus Kha’sekhem and the Horus-Seth Kha’sekhemui were one and the same person cannot be ruled out. Such a conjecture assuming that he preferred the latter form of his name while the conflict with Peribsen was still fresh in his mind, but it is a serious objection that Kha’sekheumui has monuments of his own at Hieraconpolis distinct from those of Kha’sekhem, the principal one being the great pink granite jamb of a gateway bearing on the back the scene of an episode in some important foundation ceremony. An objection to regarding Kha’sekhem as a separate king intervening Kha’sekhemui and Djoser, the founder of Dyn. III, is that a sealing found in Kha’sekhemui’s tomb at Abydos names a queen Hepenma’e is named as ‘mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt’ on a sealing in the great tomb of Bed Khallaf near Abydos where Djoser’s prominence even prompted the guess that he might be the owner. It has been consequently supposed that Kha’sekhemui and Hepena were the actual parents of Djoser. The conjecture is tempting, but if correct one is left wondering why there should have been a change of dynasty at this point. Before leaving the subject of Kha’sekhemui it must be mentioned that the making of a copper statue of his record is in the fifth line of the Palermo Stone; also that a breccia fragment with his name was discovered at Byblos.

As has here more than once been pointed out, little importance can be attached to small objects found in distant parts, but there is some solid evidence of dealings, friendly or otherwise, between these later kings of Dyn. II and the north. Not only do there exist sealings giving Peribsen the epithet ‘conqueror of foreign lands’, but there are also grounds for thinking that it was he who introduced the cult of Seth into the north-eastern Delta. Concerning the fragmentary stela of Kha’sekhem from Hieraconpolis we have already spoken; conflict with a Libyan enemy is there clearly indicated. Nothing more definite, however, can be learned about the events of this troubled period. That its kings did not fall into immediate disrepute is evident from the inscription of some mastabas at Saqqara which presumable belong to Dyn. IV. In one of them a certain Sheri declares himself to have been overseer of the priest of Peribsen in the necropolis, in the house of Send, and in all his places. More problematic are some broken pieces from the tomb of a prophet of that King Nebka whom the Turin Canon and the Abydos king-list place immediately before Djoser. This king is named also in the story of the Magicians referred to above, where, however, it seems to be implied that his reign fell between those of Kings Djoser and Snofru. From what has been already said Nebka could not have been the predecessor of Djoser and Snofru unless he were a successful rival of Kha’sekhemui. The nineteen years assigned to him remain a problem. In the footnotes to the list of kings below may be ready the fantastic occurrences attributed to the kings of Dyn. II by Manethos. It need hardly be repeated that those occurrences are drawn from the fictional literature which was evidently one of the Egyptian historian’s main sources of inspiration.

Manetho’s totals of 253 years from Dyn. I and 302 for Dyn. II of course cannot be trusted, and we must again stress the improbable nature of the 450 years which the Palermo Stone seemed to demand for the two dynasties combined. But however long or short the period, it sufficed to imprint upon the civilization of Ancient Egypt the peculiar stamp which thenceforth distinguished her remains so markedly from those of the neighboring countries. The splendid efforts of Petrie and a highly skilled body of later excavators have enabled scholars to observe step by step the material developments which transformed a semi-barbarous culture into one of great refinement and prodigious power, but in the absence until Dyn. V of adequate written evidence the corresponding intellectual and religious development have remained hidden. When at last the Pyramid Texts and other such material reveal something of Egyptian mind, many survivals of past history are found embedded therein, and the question then arises as to how far we can disentangle out of the confused and complex data the various stages which made Egypt what she had by this time become. But before discussing some of the views that have been expressed on this subject it will be well to recall what the Egyptians themselves had to say about their remote past. No explicit statement dates from earlier than Ramesside times, when the Turin Canon furnishes us with an account in substantial agreement with that of Manetho. In both authorities the oldest kings belong to the Great Ennead, that family of nine deities which the Pyramid Texts definitely associates with the theology of Heliopolis. For that reason, the list ought ot have begun with the sun-god Re’-Atum, but in Manetho, which is here alone preserved, Hephaestos, i.e., Ptah of Memphis, is placed before Helios, suggesting that this particular version was compiled in Dyn. VI, the kings of which came from that city. After Agathodaemon (the air-god Shu), lost in the Canon, there follows in agreement therewith Cronos (the earth-god Geb), then Osiris, the Typhon (Seth) the murderer of Osiris, and Horus his father’s avenger. In both sources the goddesses Tephenis, Nut, Isis, and Nephthys are omitted on account of their feminine sex, but in earlier traditions the Great Ennead included them as the consorts of four of the males, though not attributing to them reigns of their own. Concerning these purely mythical rulers no more need be said at present.

They are succeeded in Manetho by a number of monarchs described as Demigod and as Dead Ones (Greek Vekves, Latin Manes), the human Menes then following at the head of Dyn. I. The Turin Canon, which had already placed a ‘Horus of the Gods’ immediately after Seth, names a second Horus at the end of the divine dynasty, and apparently a third a little farther down. After this a number of broken lines conclude with the already mentioned ‘Followers of Horus’, these qualified as exalted spirits, the immediate predecessors of Menes. Now Seth had rightly diagnosed the Shemsu-Hor (‘Followers of Horus’) as the kings of Hieraconpolis and of Buto respectively, but by an oversight he omitted the most decisive proof of his contention. This, as Griffith pointed out orally to the present writer, occurs in a hieroglyphic papyrus of Roman date which undoubtedly incorporates a mass of traditional lore familiar to the learned of the Cheops. Here we find side by side two entries reading (I) ‘Souls of Pe (Buto), Followers of Horus as Kings of Lower Egypt’, and (2) ‘Souls of Nekhen (Hieraconpolis), Followers of Horus as Kings of Upper Egypt’. It would be impossible to find any more precise reminder of that concluding phase of predynastic history which, starting out from Hieraconpolis, ended with the conquest of Lower Egypt by Menes and with the unification of the Two Lands. In the papyrus just quoted, the word for ‘King of Upper Egypt’ (nswt) is written quite normally with the reed, and the word for ‘King of Lower Egypt” (bity) with the bee. It falls into line with the undoubted triumph of Menes that in the insibya-title of the Pharaohs the reed should have priority in the hieroglyphic writing, just as in the nebty-title of the royal titulary (ibid) the vulture-goddess of El-Kab has priority over the Lower Egyptian cobra-goddess Edjo of Buto. Odd as it may seem to readers unacquainted with old Egyptian habits, such graphic precedence must be understood as having a real historic significance. Lastly, if anyone should still doubt the reality of a predynastic line of rulers in Buto, he must surely be convinced by the isolated mention in the Pyramid Texts of the ‘King of Lower Egypt who are in Pe’, and by the fact that it was Upper Egypt, not Lower Egypt, which gave to the language its generic word nswt for ‘king’.

All these facts together corroborate and amplify what was deduced from Quibell’s discoveries at Hieraconpolis: the separate kingdoms of Nekhen and Pe were undoubted realities, as was also their unification by Menes. There remain, however, difficulties not to be lightly brushed aside. J. A.. Wilson has pointed out how unsuitable both Hieraconpolis and Buto were to become permanent royal residences, the former town lying in an arid and infertile tract near the extreme limit of Upper Egypt, while the latter town was situated almost like an island amid the watery fens of the northwestern Delta. Wilson’s suggestion is that both may have become holy cities and possibly places of pilgrimage. A much more daring hypothesis which has obtained some popularity of late must be resolutely combated. This hypothesis maintains that all the talk about the Two Lands, the contrasting of Upper and Lower Egypt, and other expressions of the kind, are no more than fiction due to a supposedly deep-rooted penchant of the Egyptian mind in favor of opposing dualistic conceptions. It is not necessary to deny the ancient people’s fondness for contrasted phrases like ‘heaven and earth’, ‘man and woman’, ‘Black Land and Red Land’, but to dismiss as simple chimeras all statements relating to the two kingdoms is to fly in the face of common sense. A less fantastic, but still wrong-headed variant of the same contention, is based upon the assumedly water-logged condition of the Delta in the centuries before Menes. It is true that before the construction of dikes and other such irrigational measures the growth of important towns there must have been difficult and restricted. Nevertheless, the possibility of a very considerable Lower Egyptian kingdom is easily proved. Particularly the western side of the Delta had important cities as Dyn. I.

The temple of Neith of Sais is depicted on a tablet of ‘Aha, and another of the reign of Djer shows a building at Dep, one of the two mounds constituting the town of Buto. A relief in the Step Pyramid of Djoser records some ceremony in connection with Letopolis (Ausim) only a few miles to the north-west of Cairo. The multitude of captured cattle seen on a slate palette implies a large population of owners. The many Delta nomes administered by the wealthy nobleman Metjen towards the end of Dyn. III evidently had a long history behind them. Osiris as the ‘lord of Djedu’ (Busiris in the middle of the Delta) is perhaps not named much earlier than Dyn. VI, but that famous religious center is mentioned together with the similarly named Djede (Mendes) in the Pyramid Texts, and we cannot expect to be in possession of the earliest testimony to their existence. An attempt to show that Heliopolis cannot have been the capital of a prehistoric kingdom is hardly likely to find many converts, even if the assertion that such a kingdom actually existed rests on a somewhat precarious basis. Lastly, the writing of the insibya-title with two separate words for ‘king’ and of the nebty-title two locally contrasted goddesses need not be construed as showing that the two kingdoms were of equal extent and importance. All that can be taken as certain is the simultaneous existence of both.