Has the mummy of the beautiful Ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertiti, wife of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, really been identified? Nevine El-Aref investigates

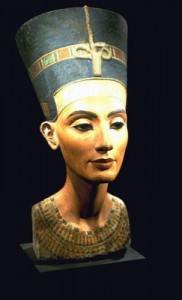

For the second time in a week, the 18th-dynasty queen, Nefertiti, has been making headlines, and has again been the subject of much discussion. After the incident in the Berlin Museum, in which the famous painted limestone bust of the queen was placed on top of a modern bronze female statue, Joanne Fletcher, a mummification expert from the University of York in England, announced that she and her team may have identified the actual mummy of the queen.

Back in 1898, the French Egyptologist Victor Loret excavated the tomb of Amenhotep II on the Theban necropolis and came upon a remarkable find. This was the first tomb ever opened in which the Pharaoh was still in his original resting place, and, moreover, 11 other mummies were also discovered in a sealed chamber in the tomb; 11 in all, nine belonging to members of the royalty family. Eight of the mummies were transferred to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and three were left in situ due to their critical state of preservation. One of this trio of mummies is now thought to be that of Nefertiti. One of the others, a female who had managed to retain her remarkable beauty, became known among Egyptologists as the “Elder Lady” and was identified as queen Tiye, the chief wife of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III. A mummy of the young prince, not identified, bears a facial resemblance to that of Tiye’s mummy, suggesting it could be Prince Thutmose, the eldest son of Amenhotep III. And as for the third mummy, known as the “Younger Lady”, the Egyptologists sway between the lovely queen Nefertiti and Princess Sitamun, a daughter of Amenhotep III (whom he may also have married and who would perhaps have been interred with her mother, Tiye).

Back in 1898, the French Egyptologist Victor Loret excavated the tomb of Amenhotep II on the Theban necropolis and came upon a remarkable find. This was the first tomb ever opened in which the Pharaoh was still in his original resting place, and, moreover, 11 other mummies were also discovered in a sealed chamber in the tomb; 11 in all, nine belonging to members of the royalty family. Eight of the mummies were transferred to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and three were left in situ due to their critical state of preservation. One of this trio of mummies is now thought to be that of Nefertiti. One of the others, a female who had managed to retain her remarkable beauty, became known among Egyptologists as the “Elder Lady” and was identified as queen Tiye, the chief wife of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III. A mummy of the young prince, not identified, bears a facial resemblance to that of Tiye’s mummy, suggesting it could be Prince Thutmose, the eldest son of Amenhotep III. And as for the third mummy, known as the “Younger Lady”, the Egyptologists sway between the lovely queen Nefertiti and Princess Sitamun, a daughter of Amenhotep III (whom he may also have married and who would perhaps have been interred with her mother, Tiye).

This is, of course, mere speculation. Some research was carried out at an early stage to verify whether the mummy of the Younger Lady was, in fact, Nefertiti, but to no avail. However, early last week, Fletcher asserted that it was indeed Queen Nefertiti. Filed under catalogue number 61072, Fletcher was able to locate this mummy, along with the other two mummies lying on the floor of a side chamber of the tomb of Amenhotep II. She was drawn to the tomb during an expedition in June 2002 when, after identifying a Nubian-style wig worn by royal women during Akhenaten’s reign, she identified a similar wig found near three unidentified mummies. This, she claimed, suggested the strong possibility of the link. If true, it would certainly have some wide- ranging implications for Egyptology.

Apart from the similarity in physiognomy, and the swan-like neck of the mummy that bears a resemblance to Nefertiti’s beautiful face as immortalised in the limestone bust in Berlin, Fletcher pointed to other clues to support her hypothesis: a doubled- pierced ear lobe, which she claims was a rare fashion statement in Ancient Egypt; a shaven head; and the clear impression of the tight-fitting brow-band worn by royalty. “Think of the tight-fitting, tall blue crown worn by Nefertiti, something that would have required a shaven head to fit properly.” Fletcher’s assertion, released on the Discovery Channel’s Web site, placed considerable stress on these particular characteristics of the mummy — the brow-band over the foreheads of Egyptian rulers, and a double-pierced ear of the mummy, which she stressed can also be seen on busts of the queen and one of her daughters.

“There is a puzzle,” she conceded, and explained that in 1907, when Egyptologist Grafton Elliot Smith first examined the three mummies, he reported that the Younger Lady was lacking a right arm. Nearby, however, he had found a detached right forearm, bent at the elbow and with clenched fingers. She said that the mummy had deteriorated badly; that the skull was pierced with a large hole, and the chest hacked away. Worse still, the face, which would otherwise have been excellently preserved, had been cruelly mutilated, the mouth and cheek no more than a gaping hole. Further examination using cutting- edge Canon digital X-ray machinery, the team spotted jewellery within the smashed chest cavity of the mummy. They also noticed a woman’s severed arm beneath the remaining wrappings. The arm was bent at the elbow in Pharaonic style with its fingers still clutching a long-vanished royal sceptre.

Following Discovery Channel’s coverage of the events, the identification of the Younger Lady’s mummy as Nefertiti immediately attracted an eager audience and made headlines around the world. But Egyptologists are not so convinced. In fact, they are divided into two schools of thought. Salima Ikram, author of The Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity, sees the identification as “interesting” and one that will doubtless cause endless speculation. Others express doubt that the remains are those of the legendary queen of beauty. Egyptologist Susan James, who trained at Cambridge University and who spent a long time studying the three mummies, told Discovery Channel, who financed the expedition, ” What we know about mummy 61072 would indicate that it is one of the young females of the late 18th dynasty, very probably a member of the royal family. However, physical evidence known and published prior to this expedition indicates the unlikelihood of this being the mummy of Nefertiti. Without any comparative DNA studies, statements of certainty are wishful thinking.”

For his part, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA) Zahi Hawass totally refutes the idea, and describes it as “pure fiction”. He accuses Fletcher of lacking in experience, as “a new PhD recipient”, and told Al-Ahram Weekly that Fletcher’s theory was not based on facts or solid evidence, “only on facial resemblance between the mummy and Nefertiti’s bust, and on artistic representations of the Amarna period in which the queen lived”.

Hawass asserted, moreover, that the physical resemblance is not significant, “because all the statues of the Amarna era have the same characteristics. Amarna art was idealistic and not realistic,” he said, and pointed out that in the Egyptian Museum, there were five of six mummies with the same characteristics. Mamdouh El-Damati, director of the Egyptian Museum, mentioned that this theory was not new, this being the second time that a claim to have discovered Nefertiti’s mummy within this group of mummies had been made.

Elaborating on his scepticism about the mummy being that of Nefertiti, Hawass told the Weekly that X-ray analysis carried out previously by himself and Egyptologist Kent Weeks indicated that it was the body of a 16-year-old girl, whereas Nefertiti is thought to have died in her 30s. He explained that, “Nefertiti was involved in the assassination of her husband’s successor, Smenkhare, and was later in conflict with King Horemhab who overthrew the monotheistic cult of his predecessor and erased all traces of it. Horemhab would never have allowed Queen Nefertari to be buried in the Valley of Kings,” he concluded.

Nefertiti was a high-profile queen, who, incidentally, appeared nearly twice as often in reliefs as her husband, the king, during the first five years of his reign. After this she continued to appear in reliefs, though outshone to some extent by other royal favourites like Kiya and her own eldest daughter Mereaten. In the latter years of the Akhenaten’s reign, however, she disappeared from the scene. So whether or not the mummy is indeed that of the beautiful queen, the dearth of convincing evidence means this may remain one of Ancient Egypt’s most enthralling and enduring mysteries.