If disproportionate space seem here to have been devoted to a single dynastic problem, the excuse must be firstly the importance of the two great personages who now face one another in the center of the stage and secondly the fact that no events in Egyptian history have given rise to such heated controversy. The aim of this book being not solely to revive the Egyptian past, but also to glance at the methods of Egyptologists, some reference to the arguments which have here played so large a part will not be out of place. The Pharaohs had the unpleasant habit of causing to be destroyed the carved names of any hated predecessors, but those name were apt to be restored later or replaced by other names. Such was the enmity excited by Hashepsowe that her cartouche was systematically erased on many of her monuments and in later times was not admitted to any king-list. A frequent occurrence is that the name of Tuthmosis I or Tuthmosis II has taken the place of hers. Who was responsible for the erasures and who for these replacements? In an elaborate essay published in 1896 and remodeled and rewritten in 1932 Kurt Sethe argued that the restorations could only have been effected by the owners of the secondary cartouches, with the consequence that both these monarchs must have returned to the throne for a brief spell after Hashepsowe’s original dictatorship; this, however, was not all, but along similar lines a novel and highly complicated theory was evolved of the entire Tuthmoside secession. In reply E. Naville, the excavator and editor of Hashepowe’s wonderful temple at Der el-Bahri, maintained that the restorations were of Ramesside date. Both views were rejected by the historian Ed. Meyer and the archaeologist H.E. Winlock, these scholars reverting to the much simpler opinions that had prevailed before Sethe had embarked upon his venturesome hypotheses. In 1933 W.F. Edgerton, after a careful re-examination of all accessible cartouches, felt himself able to maintain that nearly all the erasures and restorations were due to Tuthmosis III, whose aim was to vindicated his own dynastic claim, while Hashepsowe had the identical purpose in any cases where the names of Tuthmosis I and Tuthmosis II are original and intact upon monuments erected by her. Lastly, W. C. Hayes corroborated Edgerton’s conclusions by a study of all the sarcophagi of the period. The reflection may here be hazarded that so great a diversity of opinion suggests the extremely precarious nature of this kind of testimony; conclusions derived from erasures and their replacements are best discounted so far as possible.

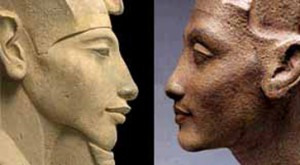

During the lifetime of Tuthmosis II the full titles borne by Hashepsowe were ‘king’s daughter, king’s sister, god’s wife, and king’s great wife’. She was still merely a principal queen like others before her, and there could be no thought of her receiving a tomb in the only an awe-inspiring spot then just beginning to be reserved for the Pharaohs. A tomb of her own dating from this period, with sarcophagus intact, was found at a dizzy height in a cliff a mile and a half southwards for Der el-Bahri. In the first years of her government she had to content herself assuming the Double Crown. Twice before in Egypt’s earlier history a queen had usurped the kingship, but it was a wholly new departure for a female to pose and dress as a man. The change did not come about without some hesitation, because there is at leas one relief where she appears as King of Upper and Lower Egypt, and yet is clad in woman’s attire. But there are various places, particularly at Karnak, where Hashepsowe is depicted in masculine guise and taking precedence of Tuthmosis III, himself indeed shown as a king, but only as a co-regent. In many inscriptions she flaunts a full titulary, though both on her own monuments and on those of her nobles she is apt to be referred to by feminine pronouns or described by nouns with a feminine ending. A still unpublished inscription places her coronation as king as early as year 2, and from that time onwards until year 20 there was no doubt as to who was the senior Pharaoh. In the latter year, however, the two are represented as on an equality.

During the lifetime of Tuthmosis II the full titles borne by Hashepsowe were ‘king’s daughter, king’s sister, god’s wife, and king’s great wife’. She was still merely a principal queen like others before her, and there could be no thought of her receiving a tomb in the only an awe-inspiring spot then just beginning to be reserved for the Pharaohs. A tomb of her own dating from this period, with sarcophagus intact, was found at a dizzy height in a cliff a mile and a half southwards for Der el-Bahri. In the first years of her government she had to content herself assuming the Double Crown. Twice before in Egypt’s earlier history a queen had usurped the kingship, but it was a wholly new departure for a female to pose and dress as a man. The change did not come about without some hesitation, because there is at leas one relief where she appears as King of Upper and Lower Egypt, and yet is clad in woman’s attire. But there are various places, particularly at Karnak, where Hashepsowe is depicted in masculine guise and taking precedence of Tuthmosis III, himself indeed shown as a king, but only as a co-regent. In many inscriptions she flaunts a full titulary, though both on her own monuments and on those of her nobles she is apt to be referred to by feminine pronouns or described by nouns with a feminine ending. A still unpublished inscription places her coronation as king as early as year 2, and from that time onwards until year 20 there was no doubt as to who was the senior Pharaoh. In the latter year, however, the two are represented as on an equality.

It is not to be imagined, however, that even a woman of the most virile character could have attained such a pinnacle of power without masculine support. The Theban necropolis still displays many splendid tombs of their officials, all speaking of her in terms of cringing deference. But among them one man stands out preeminent. Senenmut seems to have been of undistinguished birth, for in the intact tomb of his parents discovered by Lansing and Hayes, his father is given no title but the vague one of ‘the Worthy’, while his mother is merely ‘Lady of a House’. Yet in the course of his own meteoric career, he secured at least twenty different offices, many of them no doubt highly lucrative. His principal title ‘Steward of Amun’ may well have put at his command the vast wealth of the Temple of Karnak. The great favor which he enjoyed with his royal mistress is attested by his tutelage over the princess Ra’nofru, the next heiress to the throne through her mother’s marriage with Tuthmosis II. No less than six of the ten or more statues which we have of Senenmut depict him holding the child in his arms or between his knees, but though she doubtless survived until long after Hashepsowe’s magnificent temple at Der el-Bahri had been begun, nothing more is heard of her after year II. If we may believe Senenmut’s claim on the statue form the Temple of Mut, it was he who was responsible for all the Queen’s many Theban buildings, though the statement usually made that he was the actual architect lacks justification. As mentioned earlier, Hashepsowe’s funerary at Der el-Bahri situated within the grand semicircle of lofty cliffs, owes much of its inspiration to Menethotpe I’s more modest monument lying alongside it to the south. Only traces remain of the causeway sloping gently upwards to the limestone enclosure wall. Here an entrance gives access to a vast court whence the approaching visitor sees in front of him portico above portico as he mounts by a central ramp to the top level. A colonnade of gleaming white limestone to the north of the middle court enables us to envisage the beauty of the structure before time and human destructiveness had wrought the present ruin.

Even now there is no nobler architectural achievement to be seen in the whole of Egypt. The sculptured reliefs behind the columns or pillars of the porticoes are of unique interest. In the bottommost portico is a splendid scene of ships bringing two great obelisks of red granite from Elephantine to Karnak. These are believed to be those which Hashepsowe charged Senenmut to erect outside the eastern girdle-wall and which have survived only in fragments. They are not to be confused with two others which she placed between the Fourth and Fifth Pylons in her sixteenth year and of which one, only a little short of 100 feet in height, is still standing. The portico in the next tier above has even more of interest to show: on the south side the famous expedition to Pwene in year 9 and on the north the queen’s miraculous conception and birth. In the former series of pictures the ships of Queen Hashepsowe, by this time a king, are seen arriving at their destination near the Bab el-Mandeb, and being greeted by the bearded chieftain and his hideously deformed wife. Less important chiefs prostrate themselves before the emblem of the queen.

They speak, praying for peace from Her Majesty: Hail to thee, king of Egypt, female Sun who shiniest like the solar disk…. The native inhabitants lived amid palms in round -domed huts the doors of which were reached by ladders. The Egyptian envoy pitched his tent near at hand and presented gifts of beer, wine, meat, and fruit by Hashepsowe’s orders, but it is clear that her troops were to have the best of the exchange, for there are elaborate pictures of all sorts of valuables being carried to and loaded in the ships, among these products being myrrh trees, ebony, ivory, gold, baboons, and leopard-skins. In an upper register the fleet is displayed starting in the homeward direction, the necessary transportation across the desert to the Nile being ignored. the fanciful nature of these wonderful reliefs is, however, exceeded by those on the other side of the ramp. Here , by a fiction of which traces have been found as early as Dyn. XII, the monarch is credited with a divine origin. The preliminaries to the act of procreation are discreetly indicated by the figure of the Queen ‘Ahmose sitting on a couch opposite the god Amun. The next episode shows the royal infant, accompanied by an indistinguishable counterpart which represents his ka or soul, being fashioned on a potter’s wheel by the ram-headed god Chnum. The pregnant queen-mother is now led to the actual birthplace, where many minor divinities are in attendance. Much of these scenes has been erased by the later malice of Tutmosis III. It is in keeping with the tortuous workings of the Egyptian mind that the boasted father hood of Amun was not allowed to exclude that of Tuthmosis I, for there is ample evidence of Hashepowe’s insistence on this human filiation. A long inscription at Der el-Bahri invents a forma assembling of the Court in which the old king announced his daughter’s accession, and at Karnak a corresponding hieroglyphic record thanks Amun for having sanctioned the same auspicious occurrence. That these claims are fictitious is apparent both on account of the intervening reign of Tuthmosis II and because in the early days of her rule Hasepsowe was still using only the title ‘King’s Great Wife’.

A nemesis overtook Senenmut in the end. It was no unheard of thing for a Pharaoh to commemorate his leading officials on the walls of his funerary monument. Piopi II had done this at south Saqqara and Hashepsowe did the same Der el-Bahri. But it was an unparalleled step for a court favorite, however powerful, to use his sovereign’s temple for his own devotional purposes. In some of its chapels there are small niches or closets used for storing objects required in the ceremonies, and these niches had wooden doors which when opened concealed the sides behind them. Here Senenmut, hoping for his action to remain unobserved, even though he claimed to have had his royal mistress’s permission, cause to be carved images of himself praying for his royal mistress’s well-being. Unhappily this artifice became known, and the reliefs were mercilessly hacked out, only four among them by chance remaining unscathed. A similar fate befell his sepulchral arrangements. Earlier in his careen he had started upon a grandiose gallery tomb at Sheikh ‘Abed el-Kurna now almost totally ruined. But for the safety’s sake he planned to be buried in a small chamber near the northern edge of Hashepsowe’s great court, reached by a descending stairway nearly 100 yards long. this was discovered and entered by Winlock in 1927, when his portrait was found to have been mutilated everywhere, thought the name of Hashepsowe was left untouched. Even greater rage was expended on the quartzite sarcophagus that had lain near his upper tomb, fragments being found scattered far and wide over a large area.

The last that we hear of Senenmut is in year 16, but Hashepsowe herself certainly survived for five or six years more. Once she had proclaimed herself king there was no reason why she should not have a tomb at Biban el-Moluk, and this was excavated by Howard Carter in 1903. It had apparently been meant to run it completely under the cliff so as to bring it sepulchral hall right under her temple, but the crumbly rock thwarted any such intention. Two sarcophagi were found, one altered as an afterthought to receive the body of Tuthmosis I which she apparently planned to remove from his own tomb so that they might dwell together in the Netherworld. It is uncertain whether this aim was ever achieved. How she met her death is unknown, but it was not long before Tuthmosis III began to expunge her name wherever it could be found. She left many monuments behind her, but none in the north except at Sinai. According to a long provincial temple called Speos Artemidos by the Greeks, her special pride lay in having restored the sanctuaries of Middle Egypt which had remained neglected ever since the Asiatics were in Avaris of the North Land, roving hordes in the midst of them overturning what had been made, and they ruled without Re’, and he acted not with divine command down to the time of My Majesty. Doubtless the claim exaggerated and does scant justice to the merits of her predecessors.

Tuthmosis III, now a full-grown man and having a free hand at last, clearly did not intend to be outdone by his defunct stepmother, whom he resembled in his determination to obtain full publicity for his achievements. Just as her own temple at Der el-Bahri had offered its wall-space for the purpose, so he too utilized the steadily growing temple of Amen-Re’ at Karnak, this having the advantage that he could simultaneously express his gratitude to a deity who had by this time become the great national god. The sanctuary built by the first two kings of Dyn. XII had been a humble affair, but from the beginning of Dyn. XVIII much had been added, the contributions made by Amenophis I, Tuthmosis I, and Hashepsowe being very considerable. But still the Middle Kingdom edifice remained the limit in the eastward direction, while to the west the building along the main axis did not extend beyond what is now known as the Fourth Pylon. Centuries had to elapse before the vast complex of temples of which the ruins are seen today had come into being. The most conspicuous additions due to Tuthmosis III were his fine Festival Hall to the east, and the Seventh Pylon to the south, but walls and doorways of his are everywhere, all of them covered with scenes and inscriptions testifying to his piety and his victories. In the Festival Hall he even caused to be depicted the strange plants with which he had become acquainted in Syria, though the identification of these would sorely puzzle a botanist. As usual we have to bemoan the disappearance of blocks which once completed his narration, though enough is left to enable us to judge of their general trend and character. It is refreshing to find them more factual and less bombastic than the records of most other Pharaohs; here the information given can be accepted with considerable confidence. It must be noted, however, that most of the inscriptions are retrospective and were not composed until after year 40, when Tuthmosis will have been past the age for strenuous military activity. In addition to the Karnak texts there are two stele which summarize his physical prowess and deeds of valor, the larger and more important one having been erected in his far-off temple of Napata (Gebel Barkal) near the Fourth Cataract, the other from Armant, smaller and less complete, but covering much the same ground. The event to which Tuthmosis harks back again and again and which he evidently regarded as the foundation of all his subsequent successes was his victory at Megiddo, a strongly fortified town overlooking the Plain of Esdraelon. This took place in his twenty-third year, the second of his independent reign, and the story is told on some unfortunately fragmentary walls in the very center of the temple of Amen-Re’.

The reign of Hashepsowe had been barren of any military enterprise except an unimportant raid into Nubia, with the result that the petty princes of Palestine and Syria saw an opportunity of throwing off the yoke imposed upon them by the first Tuthmosis. At the head of the rebellion was the prince of Kadesh, a great city on the river Orontes which owed its importance to its strategic position at the northern end of the so-called El-Bika (‘the Valley’), the defile lying between Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon. Towards the end of the eighth month in his twenty-second year Tuthmosis III marched out of his frontier fortress at Tjel near the modern Kantara on the Suez Canal, his aim, as he tells us, being

to overthrow that vile enemy and to extend the boundaries of Egypt in accordance with the command of his father Amen-Re’.

Ten days later found him at what subsequently became the Philistine city of Gaza, which he seized; this chanced to be on the anniversary of his accession, and the first day of his twenty-third year. Gaza he left on the morrow, to reach within ten days more a town named Yehem clearly at no great distance from the mountainous ridge which had to be crossed before he could come to grips with the enemy. Here is called a council of war and addressed his officers as follows:

That vile enemy of Kadesh has come and entered into Megiddo, and he is there at this moment. he has gathered to himself the princes of all lands who were loyal to Egypt, together with as far as Nahrin…, Syrians, Kode-people , their horses, their soldiers, and their people. And he says (so they say) ‘I will stand to fight against His Majesty here in Megiddo’. Tell me what is in your hearts.

To this the officers reply: How can one go upon this road which is so narrow? It is reported that the enemy stand outside, and have become numerous. Will not horse have to go behind horse, and soldiers and people likewise? Shall our own vanguard be fighting, while the rear stands here in ‘Aruna and does not fight? Now there are two roads here. One road comes out at Ta’anach, and the other is towards the north side of Djefti, so that we would come out to the north of Megiddo. So let our mighty lord proceed upon whichever seems best to his heart. Let us not go upon that difficult road.

Fresh reports having been brought in by messengers, the king makes the following rejoinder: As I live, as Re’ loves me, as my father Amun favors me, and as I am rejuvenated with life and power, My Majesty will proceed along this ‘Aruna road. Let him of you who wishes go upon those roads you speak of, and let him of you who wishes come in the train of My Majesty proceeded along another road because he has grown afraid of us? For so they will say. The officers reply humbly: The father Amun prosper thy counsel. Behold, we are in the train of Thy Majesty wherever Thy Majesty will go. The servant will follow his Master. The above extracts will have given some idea of the style of this historic narrative, the earliest full description of any decisive battle; but without supplying missing words here and there even less could have been translated.

From this point onwards the lacunae multiply, and in places it will be impossible to do more than indicate the general drift. Tuthmosis having chosen the direct but more difficult road, swore that he would march at the head of his troops. After three days’ rest at the village of ‘Aruna he set forth northwards, carrying before him the image of Amun to point the way. Arrived at the mouth of the Wady he descried the south wing of the enemy forces at Ta’anach on the edge of the plain, while the north wing was deployed nearer Megiddo. Evidently it had been expected that he would take one of the two easier roads, and he recognized that owing to this mistake the confederates were as good as defeated already. Pharaohs vanguard now spread out over the valley to the south of a brook called Kina, when the officers again addressed their sovereign: Behold, His Majesty has come forth together with his victorious army and they have filled the valley; let our victorious lord hearken to us this once, and let our lord await for us the rear of his army and his people. When the rear of the army has come right out to us, then we will fight against these Asiatics and we shall not have no trouble about the rear of our army. Acting upon this advice the king halted his troops until noon when the sun’s shadow turned. The entire army then advanced to the south of Megiddo along the bank of the brook Kina, by which time it was seven o’clock in the evening. Camp was pitched there for His Majesty and an order was given to the entire army saying ‘Prepare yourselves, make ready your weapons, for one will engage with that vile foe in the morning’.

Rations were then served out and Tuthmosis and his soldiers retired to rest, the king sleeping soundly in the royal tent. In the morning it was reported that the coast was clear and that both the southern and northern divisions of the army were in good shape. All this had occurred on the nineteenth day of the month and we are surprised to be told that the battle was fought only on the twenty-first; perhaps this was because the auspicious festival of the new moon had to be awaited. We next hear of the king’s setting forth on a chariot of gold equipped with is panoply of arms like Horus Brandisher of Arm, Lord of Action, and like Mont the Theban.

For the last time the position of the forces is described, with the north wing to the north-west of Megiddo, the south wing on a hill to the south of the Kina brook, and the king in the middle between them. When the battle was engaged, Tuthmosis displayed great personal valor. The rout of the enemy was complete, they fleeing headlong to Megiddo with frightened faces and leaving behind them their horses and their chariots of gold and silver. Then the gates of the town were closed and they were hoisted up into it by their garments. The compiler of this graphic story now allows himself a lament: Would that the army of His Majesty had not set their hearts upon looting the chattels of those enemies, for they would have captured Megiddo at that moment, while the vile enemy of Kadesh and the vile enemy of this town were being hoisted up.

While the scattered Asiatics lay prostrate like fishes in a net the Egyptians divided up their possessions, giving thanks to Amun. But ahead of them lay a long siege, which according to the Napata stela lasted seven months. How vital this operation was felt to be is shown by some words with which Tuthmosis urged on his men to increased efforts: All the princes of all the northern countries are cooped up within it. The capture of Megiddo is the capture of a thousand towns. It cannot be denied that the description of the Megiddo battle, with its dialogues between king and courtiers, conforms to a common type, but it is nonetheless trustworthy on that account. The topographical facts have been verified on the spot by a highly competent scholar, whose only adverse criticism was than the narrowness of the road chosen had been somewhat exaggerated. It is needless here to recount the details of the siege, which we are told were recorded on a leather roll deposited in the temple of Amun. A certain Tjenen who was ‘scribe of the army’ claims in his tomb to have commemorated in writing the victories witnessed by himself, but since his soldierly careen extended into the second reign after Tuthmosis III, he can hardly have taken part in the latter ‘first campaign of victory’. The consequences of this did not lead as in Nubia to the appointment of a viceroy, the conditions in Palestine and Syria being very different. The whole of that area was occupied by small townships or principalities apt to quarrel among themselves or to enter into new combinations, and their allegiance to the Egyptian conqueror was always being shaken by the imminence of the other great powers pressing downward from the north. The temple of Karnak possesses from this reign great scenes of subjugated localities each represented by a prisoner with his arms bound behind his back, and the chief list of Asiatic enumerates no less than 350 names; and similarly the Napata stela mentions as many as 330 princes as having been engaged against the Egyptians in the Megiddo conflict. Little wonder the between year 23 and year 39 fourteen separate campaigns were needed in order to bring the entire north-eastern area into subjection. The Karnak records are more interested in the booty or tribune obtained than in the conduce of the military operations, but occasional entries throw light on the measures adopted and the policy pursued.

From the start Tuthmosis took the precaution of installing great princess of his own choosing and carrying off to Egypt their brothers or children as hostages. While the fields around Megiddo were entrusted to Egyptian cultivators and particularly fruitful districts provided the troops with welcome contributions to their rations, there are also ominous references to the destruction of crops and orchards, this doubtless as punishment of recalcitrant chieftains. A particularly noticeable feature is the supplying of the coastal harbors with provisions, suggesting that in the north at all event s equipment and perhaps also men were seaborne in ships built at a great dockyard near Memphis. All this successful organization cannot have failed to impress the rulers of the important states which might feel themselves to be threatened, and we read of gifts sent by the kings of Ashshur (Assyria), of Sangar (Babylonia, the Biblical Shin’ar), and even from the at this moment less dangerous Great Khatti (Hittites).

The real stumbling-block in the way of Tuthmosis III’s expansionist plans were, however, the forces of Nahrin, already mentioned in connection with Tuthmosis I. The crossing of the Euphrates and the defeat of the King of Mitanni were the crowning achievement of the eighth campaign in year 33. A graphic account is given on the Napata stela: My Majesty crossed to the farthest limits of Asia. I caused to be built many boats of cedar on the hills of the God’s Land in the neighborhood of The-mistress-of-Byblos. They were placed on Chariots (i.e. wheeled wagons), oxen dragging them and they journeyed in front of My Majesty in order to cross that great river which flows between this country and Nahrin. Nay, but he is a king to be boasted of in proportion to the performance of his two arms in battle–one who is crossed the Euphrates in pursuit of him who attacked him; first of his army in seeking that vile enemy over the mountains of Mitanni, while he fled through fear before His Majesty to another far distant land. Then My Majesty set up a stela on that mountain of Nahrin taken form the mountain on the west side of the Euphrates.

There are other descriptions of this expedition, but none equally circumstantial. If the route form Byblos passed through Katna, Tunip (near Aleppo), and Carchemish, the transportation of the boats will have covered well over 250 miles, and the use of four-wheeled ox-carts is a totally unexpected feature. But perhaps the victory was not so great as was painted, for two years later there was again fighting with the prince of Nahrin, though not in that country itself. Certain incidents of the homeward journey deserve a mention. The recreations of the Pharaohs tended to be no less stereotyped than their are, and we need not be surprised that Tuthmosis III, like his grandfather, betook himself to Niy to hunt elephants. Two distinct sources tell us that he there confronted a herd of no less than 120. On this occasion a doughty henchman of his named Amenemhab descended into the water and cut off the trunk of the largest of these animals. The vividly written autobiography in the same man’s tomb recounts, among other incidents, a very unusual bit of strategy on the part of the prince of Kadesh: a mare which he let loose would have worked havoc among the steeds of the Egyptian chariots had not Amenemhab run after it, dispatched it with his knife, and presented its tail to the Pharaoh. The town of Kadesh, which had been destroyed in the year 30, was then revisited and its new wall breached. Not even now was this neighborhood completely subjected, for we read of three of its villages being plundered in year 42.