The mythology of the Aten, the radiant disk of the sun, is not only unique in Egyptian history, but is also one of the most complex and controversial aspects of Ancient Egypt.

The ancient Egyptian term for the disk of the sun was Aten, which is first evidenced during the Middle Kingdom, though of course solar worship begins much earlier in Egyptian history. It should be noted however that this term initially could be applied to any disk, including even the surface of a mirror or the moon. The term was used in the Coffin Texts to denote the sun disk, but in the ‘Story of Sinuhe’ dating from the Middle Kingdom, the word is used with the determinative for god (Papyrus Berlin 10499). In that story, Amenemhat I is described as soaring into the sky and uniting with Aten his creator. Text written during the New Kingdom’s 18th Dynasty frequently use the term to mean “throne” or “place” of the sun god. The word Aten was written using the hieroglyphic sign for “god” because the Egyptians tended to personify certain expressions. Eventually, the Aten was conceived as a direct manifestation of the sun god.

Though the Aten became particularly important during the New Kingdom reigns of Tuthmosis IV and Amenhotep III, mostly sole credit for the actual origin of the deity Aten must be credited to Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten). Even at the beginning of the New Kingdom, it’s founder, Ahmose, is flattered on a stela by being likened to “Aten when he shines”. His successor, Amenhotep I, becomes in death “united with Aten, coalescing with the one from whom he had come”. Tuthmosis I was portrayed in his temple at Tombos in Nubia wearing the sun disk and followed by the hieroglyphic sign for ‘god’. Hatshepsut used the term on her standing obelisk in the temple of Karnak to denote the astronomical concept of the disk, though it was actually during the reign of Amenhotep II that the earliest iconography of Aten appears on a monument at Giza as a winged sun disk (though this was a manifestation of Re) with outstretched arms grasping the cartouche of the pharaoh.

Though the Aten became particularly important during the New Kingdom reigns of Tuthmosis IV and Amenhotep III, mostly sole credit for the actual origin of the deity Aten must be credited to Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten). Even at the beginning of the New Kingdom, it’s founder, Ahmose, is flattered on a stela by being likened to “Aten when he shines”. His successor, Amenhotep I, becomes in death “united with Aten, coalescing with the one from whom he had come”. Tuthmosis I was portrayed in his temple at Tombos in Nubia wearing the sun disk and followed by the hieroglyphic sign for ‘god’. Hatshepsut used the term on her standing obelisk in the temple of Karnak to denote the astronomical concept of the disk, though it was actually during the reign of Amenhotep II that the earliest iconography of Aten appears on a monument at Giza as a winged sun disk (though this was a manifestation of Re) with outstretched arms grasping the cartouche of the pharaoh.

Later, Tuthmosis IV issues a commemorative scarab on which the Aten functions as a god of war (a role usually reserved for Amun) protecting the pharaoh. Amenhotep III seems to have actively encouraged the worship of Aten, stressing solar worship in many of his extensive building works. In fact, one of that king’s epithets was Tjekhen-Aten, or ‘radiance of Aten’, a term which was also used in several other contexts during his reign. During the reign of Amenhotep III, there is evidence for a priesthood of Aten at Heliopolis, which was the traditional center for the worship of the sun god Re, and he also incorporated references to the Aten in the names he gave to his palace at Malkata (known as ‘splendor of Aten’), a division of his army and even to a pleasure boat called ‘Aten glitters’. Also, several officials of his reign bore titles connecting them with the Aten cult, such as Hatiay, who was ‘scribe of the two granaries of the Temple of Aten in Memphis. and a certain Ramose (not the vizier) who was ‘steward of the mansion of the Aten’. The latter was even depicted with his wife going to view the sun disk. Prior to Amenhotep IV, the sun disk could be a symbol in which major gods appear and so we find such phrases as “Atum who is in his disk (‘aten’). However, from there it is only a small leap for the disk itself to become a god.

It was Amenhotep IV who first initiated the appearance of the true god, Aten, by formulating a didactic name for him. Hence, in the early years of Amenhotep IV’s reign, the sun god Re-Horakhty, traditionally depicted with a hawk’s head, became identical to Aten, who was now worshipped as a god, rather than as an object associated with the sun god. Hence, prior to Akhenaten, we speak of The Aten, while afterwards it is the god Aten. Initially, Aten’s relationship with other gods was very complex and it should even be mentioned that some Egyptologists have suggested that Amenhotep IV may have equated Aten to his own father, Amenhotep III. Others have suggested that, rather than true monotheism, the cult of Aten was a form of henotheism, in which one god was effectively elevated above many others, though this certainly does not seem to be the case later during the Amarna period. To honor his new god, Amenhotep IV constructed an enormous temple east of the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak during the third year of his reign. The temple included pillared courts with striking colossal statues of the king and at least three sanctuaries, one of which was called the Hwt-benben or ‘mansion of the Benben’. This emphasized the relationship between Aten and the sun cult of Heliopolis. The Benben symbolized the primeval mound on which the sun god emerged from Nun to create the universe. One section of the temple appears to have been the domain of Nefertiti, Amenhotep IV’s principal wife and in one scene, she is pictured together with two daughters, but excluding her husband, worshipping below the sun disk.

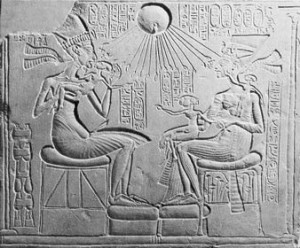

Artistically, this temple at Karnak was even decorated in a novel “expressionistic” style that broke with previous tradition and would soon influence the representation of all figures. Perhaps nowhere is this artistic style more evident then in the tomb Amenhotep IV’s vizier, Ramose. Most of the tomb’s decoration consists of fine low reliefs carved during the last years of Amenhotep III reign in a congenital Theban style, but on the rear wall of the pillared tomb is a mixture of traditional design and the startling developments in art made by Akhenaten. This new artistic style was to usher in to Egypt considerable religious upheaval. Amenhotep IV, who would change his name to Akhenaten to reflect Aten’s importance, first replaced the state god Amun with his newly interpreted god. The hawk-headed figure of Re-Horakhty-Aten was then abandoned in favor of the iconography of the solar disk, which was now depicted as an orb with a uraeus at its base emitting rays that ended in human hands either left open or holding ankh signs that gave “life” to the nose of both the king and the Great Royal Wife, Nefertiti. It should however be noted that this iconography actually predates Amenhotep IV with some examples from the reign of Amenhotep II, though now it became the sole manner in which Aten was depicted. Aten was now considered the sole, ruling deity and thus received a royal titulary, inscribed like royal names in two oval cartouches. As such, Aten now celebrated its own royal jubilees (Sed-festivals). Thus, the ideology of kingship and the realm of religious cult were blurred.

The Aten’s didactic name became “the living One, Re-Harakhty who rejoices on the horizon, in his name which is Illumination (‘Shu, god of the space between earth and sky and of the light that fills that space’) which is from the solar orb.” This designation changes everything theologically in Egypt. The traditions Egyptians had adopted since the earliest times no longer applied. According to Akhenaten, Re and the sun gods Khepri, Horakhty and Atum could no longer be accepted as manifestations of the sun. The concept of the new god was not so much the sun disk, but rather the life giving illumination of the sun. To make this distinction, his name would be more correctly pronounced, “Yati(n)”. Aten was now the king of kings, needing no goddess as a companion and having no enemies who could threaten him. In effect, this worship of Aten was not a sudden innovation on the part of one king, but the climax of a religious quest among Egyptians for a benign god limitless in power and manifest in all countries and natural phenomena.

After Aten ascended to the top of the pantheon, most of the old gods retained their positions at first, though that would soon change as well. Gods of the dead such as Osiris and Soker were several of the first to vanish from the Egyptian religious front. In fact, step by step, Amenhotep IV perused his new found religious reformation in what Egyptologists have more and more seen as a rational plan. In year six of his reign, Amenhotep IV became weary of Thebes and the old powerful Amun priesthood, and thus founded a new capital city in the desert valley area we now call el-Amarna (ancient Akhetaten) somewhat north of the old capital in Middle Egypt. Amenhotep IV mentions on two stelae that the priests were saying more evil things about him than they did about his father and grandfather, so from this we learn that there must have been a conflict that dated back at least to the reign of Tuthmosis IV. Luckily for the king, however, the priesthood was apparently not strong enough to curb a pharaoh’s inclinations at this point in time. There, in his new capital of Akhetaten (‘horizon of Aten’), Aten could be worshipped without any consideration of other deities. Thus he built both a Great Aten temple in the city as well as a smaller royal temple that could have likely also been his mortuary temple. Both were unique, having a novel architectural plan emphasizing open access to the sun rather than the traditional darkness of Egyptian shrines. Outside of Akhetaten, there appears to have also been temples dedicated to Aten at Memphis, at Sesebi in Nubia, and perhaps elsewhere during at least part of Akhenaten’s reign.

Around the time Akhetaten was founded, Amenhotep IV changed his own royal titulary to reflect the Aten’s reign, but perhaps more remarkably, he actually changed his own birth name from Amenhotep, which may be translated as “Amun is content”, to Akhenaten, meaning “he who is beneficial to the Aten” or “illuminated manifestation of Aten”. Afterwards, the king proceeded to emphasize Aten’s singular nature above all other gods through excessively preferential treatment. Ultimately, he suppressed all other deities. However, it is interesting that Akhenaten retained in his new titulary all references to the sun god Re. In his prenomen there is ‘Neferkheprure’ (Beautiful are the manifestations of Re) and ‘Waenre’ (Sole one of Re). George Hart in his Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddess tells us that Aten was:

“..really the god Re absorbed under the iconography of the sun disk. The eminence of Aten is a renewal of the kingship of Re as it had been during its apogee over a thousand years earlier under the monarchs of the 5th Dynasty.”

However, it is really doubtful that such a simple statement can be made, for in reality, Aten took on many characteristics alien to Re. Re did not function in a vacuum of gods and goddesses. Yet there remained cloudy associations with Re even as Akhenaten moved into his new capital. There, accommodations were made for the burial of a Mnevisl, which was the sacred bull of Re. Furthermore, the king’s last two daughters were named Nefernefrure and Setepenre, both incorporating Re into their names.

But indeed, Akhenaten’s new creed could be summed up by the formula, “There is no god but Aten, and Akhenaten is his prophet”. The hymn known as the “Sun Hymn of Akhetaten” offers some theological insight into this newly evolved god. We find this hymn, which may have been composed by the king himself, in the tomb of the courtier Ay, who later succeeded King Tutankhamun. Scholars have noted a similarity between the hymn and Biblical Psalm 104, although the distinct parallels between the two are usually interpreted simply as indications of the common literary heritage of Egypt and Israel. Inscribed in thirteen long lines, the essential part of the poem is a hymn of praise for Aten as the creator and preserver of the world. Within it, there are no allusions to traditional mythical concepts, since the names of other gods are absent. In this hymn, no longer are night and death the realm of gods such as Osiris and various other deities, as in traditional Egyptian religion, but are rather briefly dealt with as the absence of Aten. Hence, it should be noted that, unlike other supreme gods of Egypt, Aten did not always absorb the attributes of other gods. His nature was entirely different.

The hymn abounds with descriptions of nature and with the position of the king in the new religion. Irregardless of the existence of a priesthood devoted to Aten, only to Akhenaten had the god revealed itself, and only the king could know the demands and commandments of Aten, a god who remained distant and incomprehensible to the general populace. In fact, the priesthood may not have served so much Aten as they did Akhenaten. The high priest of the Aten was actually called the priest of Akhenaten, indicating not only the elevated position of the king in this theology, but also the effective barrier that he formed between even his priests and the god Aten. However, while the hymn seems to provide exclusive rights to the Aten only to the king, his family appears to have been included within this inner circle. The new myths of the religion were filled with the ruler’s family history and it is not surprising that the faithful of the Amarna period prayed in front of private cult stelae that depicted the royal “holy” family.

Yet, Aten was not a god of the people during the reign of Akhenaten. Far from it, in fact, considering that Egyptian religion had become more democratized around the god, Osiris. Aten had to be forced on the Egyptian people, and outside of Akhetaten (and really even there) and the official state religion, Aten never replaced all the traditional Egyptian gods. In effect, among the common Egyptians, if anything, the situation created a religious vacuum which was unstable from the beginning. And while it is clear that the elite of Akhetaten certainly paid respect to Aten, there is no real evidence for personal individual worship of the god on the part of the ordinary Egyptians whose only access to the god was through the medium of the king. On the contrary, at even the workers village in eastern Amarna, there has been unearthed numerous amulets of traditional gods, as well as some small private chapels probably dedicated to ancestor worship but showing no traces of the official religion.

Around the ninth year of of Akhenaten’s reign, the name of the god Aten was once more changed. Now, all mention of Horakhty and Shu disappeared. Horakhty was replaced by the phrase, “Ruler of the Horizon”. No longer was the hawk form of the god acceptable and this image was definitively replaced with new iconography and a purer form of monotheism was introduced. Now, Aten became “the Living One, Sun, Ruler of the Horizon, who rejoices on the horizon in his name, which is Sunlight, which comes from the disk”. Akhenaten’s new religion, which inaugurated theocracy and systematic monotheism, manifest itself with two central themes surrounding light and the king. It was probably after the god’s final name change that Akhenaten ordered the closure of the temples dedicated to all other gods in Egypt. Not only were these temples closed, but in order to extinguish the memory of these gods as much as possible, a veritable persecution took place. Literal armies of stonemasons were sent out all over the land and even into Nubia, above all else, to hack away the image and name of the god Amen.

However, even the plural form of the word god was avoided, and so other gods were persecuted as well. Yet by this time, the Amarna period had already reached the beginning of its end. Soon after the death of Akhenaten, his capital was dismantled, as was his religion. Aten was removed from the Egyptian pantheon, and Akhenaten as well as his family and religion, were now the focus of prosecution. Their monuments were destroyed, together with related inscriptions and images. While the Aten did continue to be worshipped for some period after Akhenaten’s death, the god soon fell into obscurity.